Yoga-related injuries have markedly increased during the past 15 years. We hear of shoulder issues, hip replacements, herniated discs and other physically traumatic experiences. If yoga is meant to be therapeutic, holistic and healing, what is behind these injuries? Is there something inherently wrong with the practice? Or is there something wrong with how hard and how much some of us practice?

One of the most widely recognized definitions of yoga is “Skillful Action”. If this is true, and some of the repetitive movements we perform daily in our yoga practice wear down joints and ligaments, then clearly we are not being skillful, and we are not practicing yoga.

For many of us though, the morning ritual of opening the mat is our way of connecting to our bodies and preparing our minds for the day. It helps us create a clarity and fortitude that we do not want to give up.

As Yogis, especially us in our late 20s, 30s and 40s, it would be wise to entertain the idea that all the passive stretching we are doing in yoga may not be as beneficial as we think it is. We can take heed from the experience of our senior teachers, many of whom are dealing with overuse injuries, and begin to understand that perhaps the asana practice as we know it might need a little adjusting.

In thinking about the changes that need to take place, we should understand the difference between flexibility and mobility.

Flexibility is classically defined as the ability to bend without breaking. It was once considered that the more flexible we are, the more athletic we can be and the less pain we would have. There is, however, no evidence of this being true, and some of the most flexible people are also the ones with the most pain later in life.

Mobility is our capacity to control a limb or joint through a specific range of motion. Inherent in mobility is Motor Control. Motor Control is the ability of the brain to direct a particular action through the spinal cord and into the peripheral muscles. This means that motor control is about the harmonization of the central and peripheral nervous system.

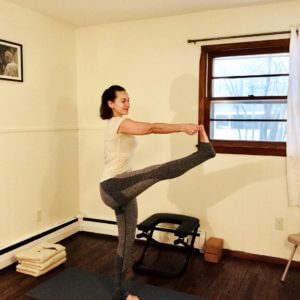

Just because we are flexible does not mean we are mobile. A great example of this is Utthitha Hasta Padangusthasana. Many of us have the flexibility to get into the pose. We bend the knee, grab hold of the big toe and straighten the leg out in front of us. We do not, however, have the ability to reach that same amount of hip flexion with our outstretched leg without the help of our hand and arm. We have the flexibility to get into the pose passively but not the ability to hold it actively.

Utthita Hasta Padangusthasana: Around 120 degrees of hip flexion

Utthitha Hasta Padangusthasana: Around 85 degrees of hip flexion (and she’s working it!)

When there is such a discrepancy in our bodies, it points to a lack of motor control capacity. Our brains are simply not able to recruit the amount of motor units required to complete the physical task. This lack of control reveals areas where our bodies and minds are not connected, and unfortunately, this is something that is rarely addressed in a typical yoga class.

There are some simple ways to assess and correct motor control functionality through yoga. Supta Padangusthasana I and II are done passively 90% of the time. We use a strap (or a hand) and get a good stretch, but rarely are these poses used to assess our joint motion and strength. Doing them actively from time to time will help hydrate the hip joint, tone the surrounding muscles and recruit many of the 1 million muscle fibers and 1000 motor nerves located in the Rectus Femoris alone.

Around 120 degrees of hip flexion passively.

Around 90 degrees of hip flexion actively.

Another example of a pose where we passively push beyond our active range potential is the lower arm for Gomukhasana. Not only do we “crawl” the hand up the back, but many use the other arm to push the hand even higher. In some situations this can be beneficial, but if it starts to challenge the integrity of the glenohumeral joint, we are doing nothing but destabilizing the shoulder. We should be mindful, especially in full range Gomukhasana, not to allow our shoulders to excessively protract. Doing the pose actively, as shown below, will help strengthen the joint capsule and the rotator cuff.

Gomukhasana lower arm full active range

Gomukhasana lower arm full passive range

Other than physically assessing one’s passive and active range potential, another sign of a motor control deficiency is chronically tight tissue. Our muscles all work in relationship with each other. When something is persistently contracted there will most often be its counterpart, something else that is persistently inhibited or neurologically underactive. In these situations, identifying, activating and strengthening the inhibited area is just as important as stretching and releasing the tight tissue.

The development of motor control helps make our bodies more resilient. Actively taking our joints through their full ranges builds articular strength and connects our bodies and minds. It is not that passive stretching is wrong, but when it is all we do, our bodies become imbalanced breeding grounds for injury. Taking the time to assess strength and train motor control will have a profound effect on our practice, both short and long term.

This is a very interesting article. How much active vs. passive work would you recommend? How do I know if I’m doing too much passive stretching?

Great blog post, Jory!

This was EXCELLENT!!!

Hi! Many thanks 🙂 Excellent article.

Thank you for sharing. This is a succinct article which really articulates what I am feeling in my yoga body as it moves into it’s 6th decade.

Interessante!